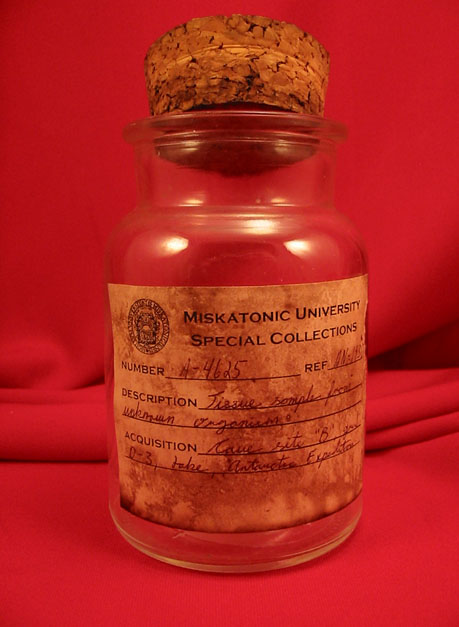

There’s nothing quite like a preserved bit of nastiness in a bottle. A specimen floating in murky liquid in a dirty sample jar just calls out to people. They want to pick it up, turn it around, and take a good look at what’s inside. The ickier it is, the better.

This tutorial will show you how to make a gruesome bit of preserved tissue using cheap and readily available materials. When you’re done you’ll have something like this:

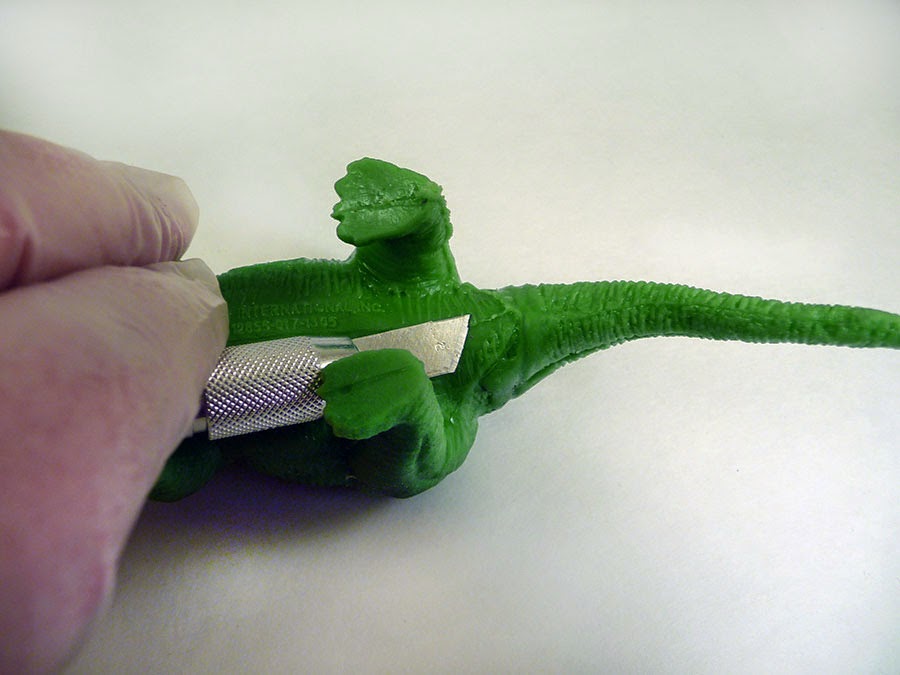

This tutorial builds on ideas originally shared by “Ravenworks69” in the Halloween Forum. To start off, you’ll need one of the soft, squishy animals frequently found on discount store shelves in the toy section for around a buck. This will be the core of the tissue specimen.

Now grab a sharp hobby knife, cackle madly, and prepare to do some surgery. You need to cut the critter open to scoop out it’s guts and turn it inside out. These squishy animals are filled with small polystyrene beads. Feel around until you find the bottom of the internal cavity that holds them. There will usually be a seam along the body at this location.

Note that I’m wearing protective gloves. What, you want me to perform surgery without taking the most basic precautions? Are you some kind of barbarian?

Once you find it, make an incision into the cavity and remove the little plastic beads inside. A shop-vac will make this considerably easier, since the little spheres are amazingly sensitive to static electricity and cling to everything.

Once the beads are out, remove the tail and turn the whole creature inside out.

To keep our specimen from floating to the top of the specimen bottle we need to weigh it down a bit. Why? Because the flexible vinyl of the dinosaur, and the other materials we’ll be adding, all float. We need to add enough mass to make the final creature neutrally buoyant. Decorative glass gems are perfect for this, since they’re cheap and totally water safe. Push two or three into the cavity you created when you turned the animal inside out.

Now we need to bulk up the body. Hit up the sewing section of your local megamart and you’ll find bags of polyester fiberfill for a few dollars. Each bag has enough stuffing for one pillow, or hundreds of our little floating nightmares. Pack the interior cavity with as much stuffing as possible. Don’t be shy about stretching the vinyl- you want it to give the specimen some heft and body. The blunt end of a bamboo skewer makes a handy tool for packing in the polyester fibers as tightly as possible.

Once you’re done you’ll have a plump little sausage of vinyl filled with glass and polyester. Hey, isn’t something missing?

That’s right, the tail. We’ll stick that through our incision to add some more texture. Coiling the length of the tail around on itself gives a good approximation of the organic shapes of real tissue.

Now it’s time to give our specimen some skin. For that we’ll be using a mixture of acrylic craft paint with Capitol brand latex carpet adhesive, available at any Home Depot. The paint provides the coloring while the latex forms the water-safe skin. All together both the paint and latex will cost around five bucks, but you’ll have enough to skin about a dozen small to medium specimens.

Since the dinosaur was bright green I picked a dark ivy green to provide a complementary color. Any color of paint will tint the latex, but darker colors provide a stronger coloration. Experiment with color combinations as you see fit.

If you can’t get Capitol, any pure latex will do. You could spring for moldmaking or mask latex, but it’s considerably more expensive per ounce than off the shelf carpet adhesive. Just make sure it’s latex based. If it is, you’ll get an eye watering whiff of ammonia when you open the top. Ventilate appropriately.

Oh, and they’re not kidding about the “adhesive” part. If latex drips onto your clothes or carpet you will never, ever get it out. Dress in old clothes and prepare your work space with that in mind.

Mix around two heaping tablespoons of the latex with a teaspoon of the acrylic paint in a disposable cup. You want to thoroughly spread the pigment throughout the latex. A bamboo skewer or popsicle stick makes a good stirrer.

Keep stirring until the mixture is uniform. The ammonia fumes will be quite strong, so ventilate appropriately.

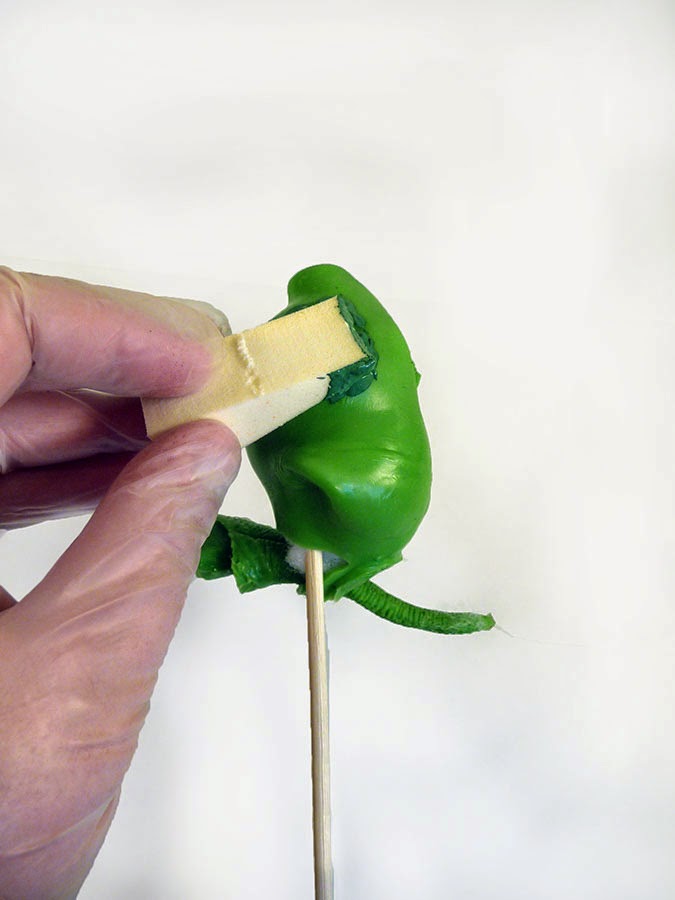

Now we apply the tinted latex to the core of our specimen. A foam makeup wedge is ideal for daubing the mixture on. You want a thin, overall coat so the latex can dry quickly. Don’t worry if you miss a spot here and there- we’ll be covering that up with additional layers of latex. I’ve mounted the specimen on the end of a bamboo skewer* to make it easier to hold. Stick the end of the skewer in a cup filled with rocks or some of your leftover glass gems to hold it in place.

*Yes, I love bamboo skewers. They really do have a million uses.

Once you’ve covered the specimen allow the latex to thoroughly dry. That can take a few hours in the open air, but sticking it in front of a fan can cut that time down to minutes. Remember, thin is the key. You should treat the latex almost like a thick paint, applying each coat as thinly as possible. Here’s what you’ll have once the first layer dries.

Now apply another layer of latex, And another. And another. In all I gave this piece six coats of latex. Let each coat dry before applying the next. If you daub on the latex with a sponge you can build up some really cool surface texture by taking advantage of the material’s natural tackiness.

After applying multiple coats of latex it’s time to rub some of it off. Poke the latex skin with the tip of a skewer or the end of a narrow-handled paintbrush, anything that will bite into the latex a bit. The end of this cheap craft paintbrush has a mold line flange that’s perfect. Then rub against the latex in small circles. As you apply pressure the latex it will eventually tear away from the vinyl and create a circular opening. Insert your tool into the hole and keep rubbing it in circles to widen it.

How cool is that? You get a neat little pustule effect. Repeat as needed to create a nasty, diseased appearance.

In one fell swoop you’ve added some interesting visual and textural contrast to the piece. The smooth exposed vinyl contrasts nicely with the gnarled surface of the latex. Our next step is going to kick up that surface treatment another notch. We’re going to drybrush the latex with a contrasting color to bring out the details.

If you’re not familiar with drybrushing, you load a stiff brush with paint, wipe most of it off on a piece of scrap paper, and then lightly run the brush along a textured surface. The tiny amounts of pigment left on the bristles of the brush stick to the raised areas, producing highlights. Here’s our specimen after being drybrushed with yellow.

Here’s a closeup of the skin. See how the yellow pigment clings to the high spots? That’s how drybrushing adds depth and detail.

Now you just drop the specimen into a jar filled with water, add a few drops of food coloring and…tada!

Okay, I did skip a few steps there. But not many. Rinse out your jar with a weak bleach solution to sterilize it, then fill it with water and drop the finished specimen in. Gently press out any air that’s trapped inside the specimen. That should leave your “tissue” sample floating gently along the bottom or side of the bottle.

Food coloring is ideal for tinting the water inside your specimen jar. I used yellow, which was a bit of a mistake. It goes nicely with the green, but it also negates the yellow highlighting I spent all that time on. I should have dry brushed with white instead.

I also added some sediment to the jar by sprinkling in a little garlic powder. The granules absorb some of the water and swell up, producing a reasonable facsimile of the detritus that flakes off organic specimens over time. Here’s what it looks like when you give it a good shake.

Finally, I added a wax seal. This is just bog-standard paraffin melted in a double boiler. I dipped the lid of the jar in the wax, set it aside to cool, and then repeated the process until the full seal was built up. Then I grunged it up with some wax-based schmutz.

There you have it. A couple of bucks for materials, a few hours of your time, and you can start populating your shelves with all sorts of bottled nastiness. There are a multitude of refinements you can add to this basic technique, from labels and collection tags to using different squishy animals as a base. Want a facehugger from “Alien”? Trim the body of a rubber spider and hot glue part of a rubber snake to it.

One of the advantages of making a “thing in a bottle” is that you can control how visible the creature inside is. If your specimen looks amazing just add some food coloring and show off your work. If it’s not that hot, some sediment and a pinch of chalk dust makes the fluid more opaque and covers up any flaws.

July 7 marked the release of the new Balzac album, Bloodsucker. And since then, I have spent some time with this album.

July 7 marked the release of the new Balzac album, Bloodsucker. And since then, I have spent some time with this album.